If you’re tired of the Aussie dominance in cricket, Sumit Narayanan and Sanchit Maini may have the right tonic for you.

The two actuaries — the people who help companies choose the best insurance deals to offer customers — have taken a break from calculating mortality figures to devise a new formula to determine one of cricket’s most debated statistics: batting averages.

And their system is bad news for the Kangaroos.

Traditionally, batsmen’s averages have been calculated by dividing the runs scored by the number of innings played. The denominator, however, omits the number of unbeaten innings. The argument is, one can’t know how many more runs the batsman might have scored had he batted on. For instance, if a batsman has scored 200 runs in five innings while remaining not out once, his average is calculated as 200/5-1, that is, 50.

It’s long been argued that this formula is biased in favour of batsmen who come later in the order. It also rewards “selfish” players who down shutters while batting with tail-enders, and punishes those who get out while throwing their bat around for the team’s sake.

The algorithm developed by Narayanan and Maini — published in the May edition of the actuarial journal The Actuary — tries to correct this. “The challenge was to somehow incorporate the ‘not out’ innings into the batting average while accounting for the fact that the batsman could have scored more had the innings continued,” Narayanan said over the phone from Singapore, where he works with actuarial multinational Watson Wyatt.

The new method includes the unbeaten innings in the denominator. But to be fair to the batsman, it gives it a fraction value.

This is done by comparing the average number of balls (ANOB) the batsman faced in an innings over his career with the number of balls he faced (NOB) in an unbeaten innings. Divide NOB by ANOB to get the “weightage” of the innings.

“If a batsman faces an average of 50 balls an innings, and faced 25 while remaining not out, this (unbeaten) innings would be considered half an innings (weightage 0.5),” explained Maini, vice-president of Max New York Life India.

If NOB equals or is more than ANOB, the weightage given is 1. The runs are now divided by the number of innings, which include the sum of the weightages for all the unbeaten innings.

To continue with the earlier example, suppose the batsman faced 20 balls in his lone unbeaten innings and that his ANOB is 50. So, the weightage given to the unbeaten innings is 20/50 or 0.4. His revised average becomes 200/4.4, that is, 45.4.

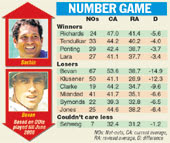

So who’s the better one-day batsman, Sachin Tendulkar or “finisher” Michael Bevan? The Australian’s average, calculated conventionally, is nearly 10 more than Sachin’s. But the new formula puts the Indian ahead.

Michael Clarke, whose average drops by nearly 10 runs, and Andrew Symonds join Bevan among the top-rung Aussies who slip a few notches. Other famous finishers such as Dean Jones and Javed Miandad — India’s nemesis for several years — suffer, too.

Not so Virender Sehwag but then, staying unbeaten is clearly not his forte.

Topping the one-day averages under the new method is Viv Richards with Sachin and Ricky Ponting following him.

“Those whose averages drop the least are the ones whose statistics haven’t been bloated by not-outs,” Narayanan says.

But the method has a flaw. What if the batsman faces more balls than his ANOB in an unbeaten innings? The weightage is a full 1, that is, no allowance is made for an unbeaten innings.

In other words, the system punishes a batsman for playing a long, match-winning innings and finishing the game. The Bevans and Joneses may, indeed, have reason to feel short-changed.

Former cricketer and coach Sandeep Patil puts it in perspective for those preparing to celebrate the “fall of the Aussies”.

“The Australians whose averages suffer are the finishers. That they remain not out so often means they generally take their team to victory. If our numbers 5, 6 and 7 don’t have many not-outs under their belt, should we be celebrating?” he laughs.

Currently, Narayanan says, the formula is suited only to one-day internationals. “In Tests, batsmen stay not out much less often.”

But the two are working to find a modified formula for Tests. When they succeed, one Brian Charles Lara, prone to play long innings but still get out, may have another feather to add to his many-hued cap.